“These hundreds of islands appear to have been designed to supply the need of a beautiful place.””

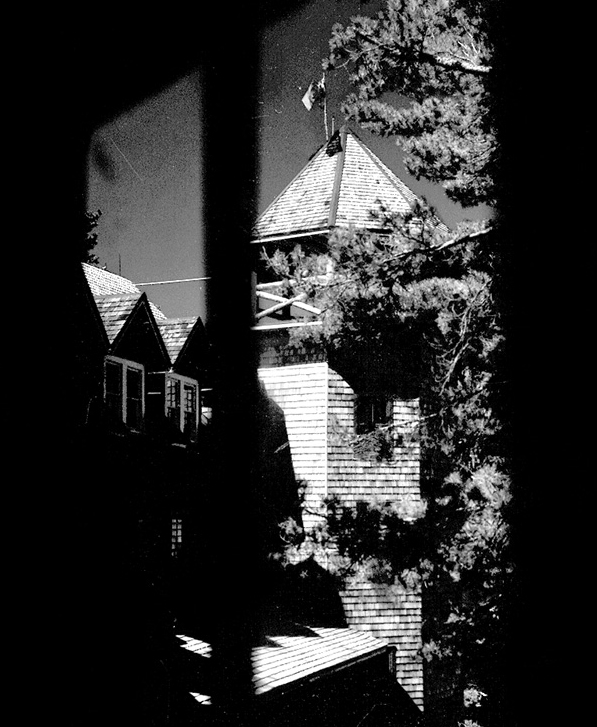

A 1939 photograph shows the hotel as it has looked for years – with claude bragdon’s tower, the stately veranda, the central steps and the stone chimney visible among the pine trees. The long wharf is ready to receive the City of Dover or the Midland City, and, at the west end of the dock, the grocery store is open, as it always was, ready to sell its Neilson’s ice cream, its bread from Forth’s Bakery in Parry Sound. At the east end, the hardware store and repair shop sold its Moore deck paint and spar varnishes, and its Olympene antiseptic liniment (“Soothe sunburn instantly!”).

For holidayers “sharp-set with hunger and desirous of appeasing it before embarking,” meals were offered on the Pointe au Baril dock at Gordon Jacobs’ CPR restaurant.

The photograph appeared in the first edition of The Ojibway Islander, a newsletter published in the summer of 1939. Its editor, Hamilton Davis, wrote: “This summer at last I am publishing five numbers of the Ojibway Islander and hope that the Pointe au Baril population will consider the paper their own and send in news items, jokes, etc. to add pep.” Each of the five issues carried the news of the day, information for travelling guests, social announcements and photos. In the June 1st edition, hotel guests read that “the four-piece orchestra of Toronto University boys will pep up the music at the Ojibway dance hall this summer” and that Dr. R. C. Dickson of the Toronto General Hospital would be the Ojibway’s resident physician.

The newsletter also reminded guests that as usual in the summer season, the CPR sleeper to Pointe au Baril would leave Toronto every Friday evening from June 30 to September 1. In marked contrast to today’s hectic, highway-clogged “rush” from the city, weekend visitors in those days boarded the northbound train, which left Toronto’s Union Station at 11 p.m., and retired to their berths for the night. The Pullman car was disconnected from the rest of the train at Pointe au Baril Station and shunted to a peaceful siding, so that the passengers did not have to disembark until morning. “A great arrangement,” recalled Mary Richardson, the daughter of Senator Peter Campbell and his wife, Mary (Babs). “It was fun to go in with Mum on Saturday morning to pick up Dad and have one of Gordon Jacob’s super breakfasts before heading out to the cottage.”

Although Hamilton Davis intended it to become a fixture of hotel life, The Ojibway Islander (far left) was published for only one summer – the summer of 1939. By the time the Second World War began, the amusing articles about fishing trophies, blueberry outings, dances and evening entertainment were the last things on anyone’s mind. People were reading about more important events – and the Islander disappeared forever. Still, summer life went on at the Ojibway. An article in the Parry Sound North Star (left) describes the delights of the hotel’s annual masquerade ball.

Gordon Bongard, a former employee of the Ojibway and a cottager, remembers some of the stories that were told about these infamous weekend trips. “The Friday-night train was bad news. After dinner and some drinks in the city, they would board the train and have a few more drinks.” Late Sunday night, the same group of businessmen boarded the hot and stuffy Pullman car that had been parked on the siding over the weekend and then hooked to the southbound train. All would be back in their offices on Monday morning.

The Ojibway Islander reported that the dance hall “was the scene of a colourful event on Saturday evening…when the yearly masquerade drew a large crowd of revellers and spectators from the Ojibway and neighbouring islands…. The Ojibway laundry staff did a clever impersonation of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs with Mrs. Battersby outstanding as the queen.” For some weeks that summer, the trophy for the largest bass sat, once again, on Mr. and Mrs. Pardoe’s table in the dining room.

The Ojibway’s cottages provided a more private holiday away from the bustle of the hotel – (left to right) Basswood, Maplewood, Birchwood (built the earliest, in 1906) and Elmwood.

As news in the Ojibway Islander reveals, the hotel was firmly established at the centre of many Pointe au Baril summer lives. And its success, with guests and islanders alike, was based, to a considerable extent, on a single guiding principle. Things could only be allowed to change very slowly at the Ojibway.

Hamilton and Irene Davis had always tried to ensure that returning guests were made to feel that their holidays would adhere to the same gentle pace as the year before and the year before that. People liked to take the same room or rent the same cottage: some families preferred Basswood, located on the water’s edge; others favoured Elmwood, set back among the trees. Each winter, Hamilton Davis would routinely phone his long-time guests to confirm their usual room or cabin for the following summer. Eleanor Kerr remembers her father coming home from the office one evening in the early 1930s with surprising news. The family would not be able to stay in Maplewood, their usual cabin, that summer. The Kerrs had been guests at the Ojibway since 1908. Their eldest son, Robert, was the first baby to stay at the hotel. Even so, they had to move from their cottage to make way for a celebrated Canadian artist.

Lawren Harris stayed at the Ojibway that summer, with his wife and three children. Eleanor, who was just 10 years old, remembers watching Harris with some resentment and curiosity, as he made his way from Maplewood to the dock early each morning with his sketchbooks. Eleanor’s brother Robert, on the other hand, was more welcoming. He took the Harris’s beautiful daughter to the Saturday-night dances.

Honeymooners Cleveland Thurber Jr. and Elizabeth Mary Hamilton, married in June 1940, availed of one of the romantic “tower rooms” of the Ojibway.

{ Love }

AFFAIRS OF THE HEART

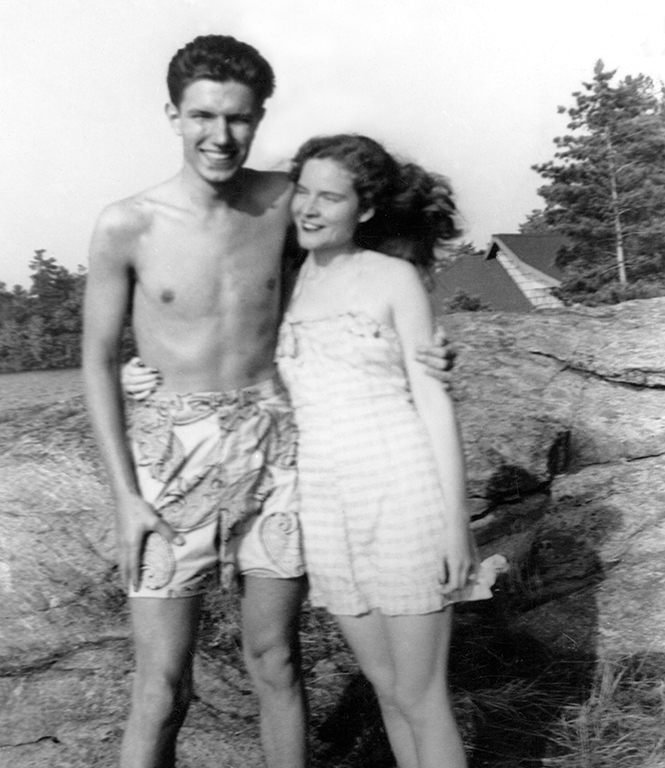

It was the place in Pointe au Baril where couples danced cheek to cheek, and where young men took their best girls out for moonlit paddles. There have been weddings and honeymoons. It was the place where glances were noticed, kisses were stolen, proposals were made and love affairs whispered about. It was a place that was so interesting, in fact, it was said that an elderly cottager kept the telescope on her island trained toward the dock so that she could keep track of the goings-on.

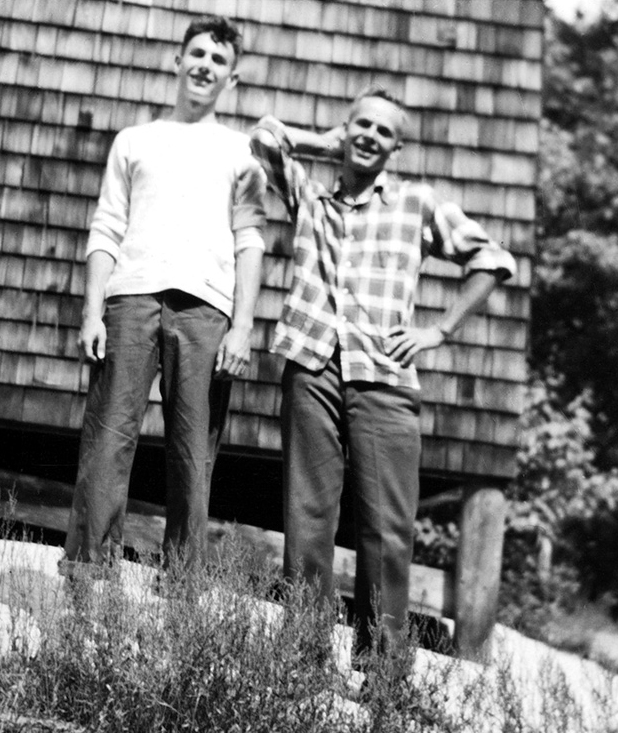

The staff has always been young, as have many of the islanders who find their way to the Ojibway. As a result, the Ojibway’s romantic stories are often about the sweet passage to adulthood that, no matter how awkward, remains for many the fondest of memories. John Evans, a long-time islander, enjoys telling of the time in the 1950s when he and his friend John Creelman managed to convince two beautiful college girls to go out for an evening cruise in their “fancy cedar-strip 35-horsepower.” The girls were both working at the Ojibway, and, as Evans tells the story, the foursome found themselves caught by a thick fog in one of Pointe au Baril’s back channels. Not such bad luck, as it turned out – at least as far as the boys were concerned. “Creelman and I were not famous for our success with startling blond coeds.” But the lucky boys were unable to do anything except drift and “spoon” with “UCLA’s most beautiful princesses” until the fog lifted.

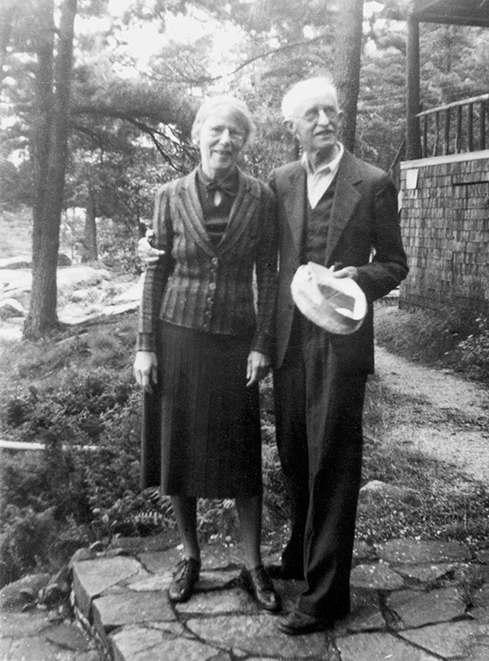

Irene and Hamilton Davis were, simply, the Ojibway. For 25 of the 30 years of their married life, they shared the responsibilities of running a busy summer hotel.

Summer after summer, the bellhops carried firewood to the cottages when the weather turned blustery, and kept the iceboxes filled. On cool nights, fires were lit in the stone fireplaces in the main building, and on Sunday evenings, singalongs were held in the lounge. On sunny mornings, while the smell of bacon and toast still drifted along the pine-needled paths, the clacking discs of the first shuffleboard match of the day could be heard from among the trees behind the hotel. On rainy afternoons, the busy rhythms of Ping-Pong in the games hut marked the time. On the veranda, the loudest noise was the rustling of a newspaper from one of rocking chairs, the thrumming of the bridge players’ shuffled cards or the mutterings of “fifteen-four, fifteen-six…” from the cribbage table. When entering the dining room for their meals, guests were met with the scent of fresh rolls and the sweet-grass placemats.

Summer after summer, Hamilton and his wife, Irene, sat at the same table in the dining room for their meals; the table was near the swinging kitchen doors and positioned so they could keep an eye on everything. Summer after summer, Bert Bruckland and Albert Desmasdon were fixtures on the Ojibway dock, and summer after summer, the fishing guides took customers to the secret shoals and back bays, preparing the same shore lunch of fish, home fries and baked beans.

Things seemed the same as ever in Pointe au Baril as one reads through the June 1939 edition of the Ojibway Islander, but here and there were hints of a gathering storm. Milton M. Brown, a friend of Hamilton Davis, wrote a letter from Antwerp and Belgrade only a few months before Hitler’s invasion of Poland, commenting on the changes already apparent to him as he travelled through Europe. He wrote of “strain and shock and foreboding” and contrasted these with the comforting sense of permanence conjured by his memories of Georgian Bay. “Can we once more sit…and watch one of those glorious, indescribable sunsets fade to soft blue twilight and the twilight deepen into night as one by one the old familiar stars come out…in one of those nights of Georgian Bay that are unlike anything the world over? Is it possible again to find the peace of that spot that our fathers discovered and taught us to love?” In Brown’s letter, just next to the photograph of the Ojibway Hotel, he wrote: “It is a happy dream. A fairy tale of our youth.”

For years, Albert Desmasdon made things work at the Ojibway. Not only did he look after the boats, he was in charge of all maintenance. Everything from generators to ice came under Albert’s purview. It was Hamilton Davis who funded his two years of mechanical training.

It is impossible to know how many snapshots of happy summers in Pointe au Baril were tucked into the kit bags of servicemen who longed to return to the holidays they had known as children. The carefree summer days at the cottage or at the Ojibway must have often seemed a distant and unattainable dream during those dark war years.

No longer could people assume that things as happy, as carefree and as innocent as summer holidays had any meaning in the world. Some families, such as the Kelks of Toronto, who had three sons away in the service, stopped going to their cottage throughout the war. Others, such as the Kellers of Oakville, Ontario, whose cottage was on Eureka Point, just to the east of the Ojibway, continued to go up despite the sadness that had fallen over them. Their 22-year-old son, Bud, had received his commission from the RAF and had last been stationed in England. Since 1940, he had been missing in action, and the Kellers returned to Eureka Point, as if in the hope that he might tie up the boat at their dock one day and reappear on the path, returning from the Ojibway with the mail, a newspaper and some groceries, as he always had for so many summers.

In the early years of the war, talk on the Ojibway dock was often of the American journalist Ernie

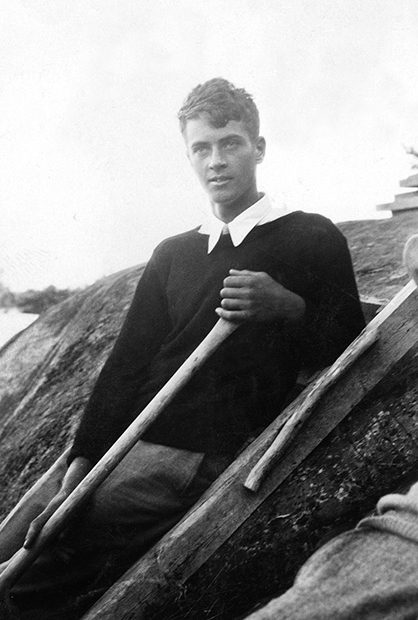

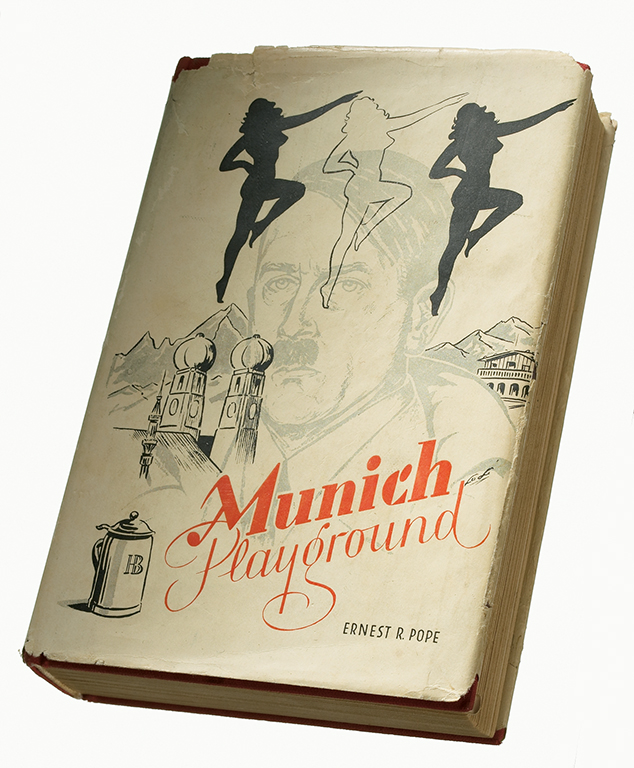

Pope. He’d been a well-known figure in Pointe au Baril – famous, as a teenager, for jumping into the water from the roof of the Ojibway’s old boathouse and, on one memorable occasion, driving a motorcycle over the paths of Ojibway Island. Ernie Pope, filing as a freelancer for Reuters news agency, was one of the few Americans reporting from Germany. His observations of the sinister intentions of the Nazis were eventually published in his first book, The Munich Playground. His sister, Elfrieda, who was also living in Germany during the anxious months leading up to the Second World War, informed her Pointe au Baril friends of her experience. “So it is,” she wrote, early in the summer of 1939, “that I dream these days more than I have for years of the heavenly seclusion of Georgian Bay.”

As a teenager, Ernie Pope (above) spent his summers at Pointe au Baril, later travelling to Europe as a journalist during the Second World War. Bud Keller had also vacationed on Georgian Bay and, when he went missing in action, was flying a Wellington bomber (pictured above, left).

On September 3, 1939, Ruth McCuaig and a gathering of other cottagers heard Neville Chamberlain’s crackling voice over the wireless on a Pointe au Baril island. A week later, on September 10, Canada joined Great Britain in the war. Twenty-seven months after that, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Nothing would be the same again.

During the war years, trips to the Ojibway post office for mail were, for many families, daily undertakings – an expedition that took on a new sense of gravity and apprehension as the war continued. Mail – from “somewhere in England,” or written in North Africa, Italy, France, Belgium or Holland – was never just mail: it was evidence that a loved one was alive and well. And the mail that was dropped off at the Ojibway and read, weeks later – in canteens, or airfield barracks, or the backs of troop trailers, or the basements of bombed-out farmhouses, or the galleys of convoy escorts – was evidence, almost unbelievable to the soldiers, airmen and sailors who opened the envelopes so eagerly, that the peace and beauty of Georgian Bay summers still existed.

In Pointe au Baril, rationing coupons were required at the Ojibway for the purchase of butter, sugar, coffee and gas. Stuart Playfair, in a wartime letter to the Islanders’ Association membership, wrote: “Our American members should obtain food-ration books at port of entry so as to avoid inconvenience.” But rationing was not a great hardship. Life went on, as before, with some restrictions. As Roger Warren, a long-time islander, remembers: “During the war, you had to document and make a guesstimate of how much gas you needed, and you got an allotment. So we could do one trip a day to the Ojibway and back. And that was it.”

During the war, life at the Ojibway revolved around letters from loved ones, ration coins and coupons, and dances where the young men were usually a little younger than

the girls might have wished. Still, aside from the worry

and the anxiety about the news from overseas – which was sometimes almost unbearable – it was no great hardship being up north for the wartime summers.

At the Ojibway’s weekly dances, there was a noticeable dearth of men. They were often dateless affairs for the girls who attended them, but cottager Suzy Haas Stohn remembers that they “were always nice to the younger boys.” At the end of one Sunday-evening concert in the lounge, the hat was passed “in aid of the overseas cigarette fund.”

There were also concerts in the movie hut, as Elizabeth Keiser recalls. During the war years the strains of “There’ll Always Be an England” competed with “Big Bass Blues” and “Ojibway Rocking Chair Fleet.” Regular guests, some of whom had been coming to the Ojibway for decades, still returned throughout the war, and even in the immediate postwar years, the hotel’s long-established traditions continued. Alan Thomas had been an Ojibway guest from 1938 to 1943 and then a staff member from 1944 to 1948, and his recollections of hotel life are not ones of enormous upheaval. He remembered that, as always, “the boat trip to the Ojibway Hotel was provided in a wonderful, sedate, cabined boat run by the Reid family” and that “it took about an hour to get to the hotel, out through the islands, which made it all magical for me.”

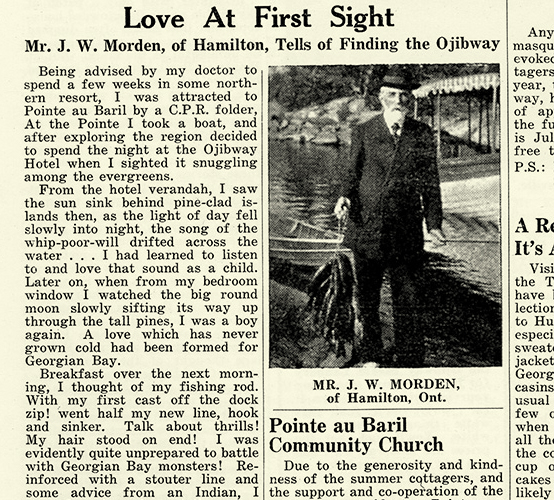

Still, some key changes in the life of the Ojibway Hotel were already becoming apparent. In the Ojibway’s newsletter of July 15, 1939, a photograph of long-time guest J. W. Morden of Hamilton, Ontario, appeared on the front page. The photo showed a man with a dignified white beard, in a heavy double-breasted suit, shirt and tie and fedora. He is standing beside a rowboat tied to the Ojibway dock and holding an impressive string of bass, looking for all the world like a figure from the Victorian age. And effectively, he was. He had come to the Ojibway 29 years earlier, and he well remembered the first night of his first visit: “From the hotel veranda, I saw the sun sink behind pine-clad islands. Then, as the light of the day fell slowly into night, the song of the whippoorwill drifted across the water…. I had learned to listen to and love that sound as a child. Later on, when from my bedroom window I watched the big round moon slowly sifting its way up through the tall pines, I was a boy again. A love which has never grown cold had been formed for Georgian Bay.”

“The trip out to the islands felt like we were going off

the edge of the world.””

If the figure of J. W. Morden – like so many of the Ojibway’s long-time guests – cast back to the Ojibway’s past, there were signs in 1939 that the summer population at the Ojibway Hotel was not being replenished by a younger generation – a trend that, for obvious reasons, was exacerbated by the war. In the same newsletter that featured J. W. Morden’s Dickensian image, an odd note appeared at the beginning of an article. The piece was intended to be the first instalment of a regular column, but it never appeared as a column again: “We are told that this,” so the anonymous columnist wrote of the assignment at hand, “is to be about the younger set of Pointe au Baril. After all, what would Pointe au Baril be without its younger set? Quieter. But in the meantime, things have still to be organized this summer; a great many of our worthy members have yet to arrive. Somehow, no younger set is complete without its members.”

At the same time that Mr. J. W. Morden (below), a figure who looked almost Victorian in his formality, could eloquently reminisce about his first summer at the Ojibway, the conversations of the young men who gathered at the hotel frequently turned to the subject of when they would enlist.

At a time when a more ordinary summer would be winding to its close and young people would be helping to put shutters on cottages, exchanging winter addresses with their summer friends and looking forward to college, everyone’s attention was on the news from Europe.

Meanwhile, Hamilton Davis had something else on his mind. By 1942, he was 78 years old and finding the demands of running a hotel too tiring. He spent most of his time in Cedarwood, a quiet cottage on the east end of Ojibway Island. The once energetic, enterprising manager sadly noted to his niece: “It’s like being shut up in prison staying down at that cottage for most of my meals. But [I] sit here and make notes for what is to be done.” Whenever he went up to the hotel, he preferred to go by rowboat, to save his legs the rough walk. Irene, his inexhaustible wife, continued to work daily, keeping the guests entertained from seven in the morning to nine at night. And Jack Cloke, Irene’s nephew, was taking on much of the day-to-day management of the hotel. We may guess that Hamilton stewed on his decision for the first few years of the war. But he made up his mind that it was time to retire and that he would offer the Ojibway to the islanders. “I have sold the hotel,” he wrote to his niece, Frances Davis, in July 1942. “But it was time I quit. I have worked 64 years, and now the cottagers have bought it.”

In 1942, Hamilton Davis wrote a postcard to his niece, Frances Davis, telling her he had sold the hotel that he loved so much. Standing on a Pointe au Baril shoal, Hamilton (top, at right) poses with Albert Desmasdon. Irene Davis (above) at the helm of her launch, Jerireneham. The name incorporated the names of her family: Irene, Hamilton, and their son, Jerry, who died at the age of five.

Peter Campbell, a former president of the Islanders’ Association, was instrumental in organizing the Ojibway purchase. In 1943, his wife Babs noted in her journal: “Peter, Roy Warren, Stuart Playfair, Sam Rogers were elected directors and president of the new Hotel Association.” But even though many of the purchasers were businessmen, their primary motive was not profit. They wanted to avoid the kind of radical change that a new owner, unfamiliar and unsympathetic with the community of Pointe au Baril, might bring to the hotel. They were interested in maintaining the beloved old property. But primarily, they were interested in doing what Hamilton Davis had done so effectively over the years: avoid change. They wanted to preserve the role that the Ojibway had played for almost four decades in Pointe au Baril summers. It was not, from a fiscal point of view, an entirely rational investment. Indeed, it was a transaction inspired far more by the heart than by the bottom line.

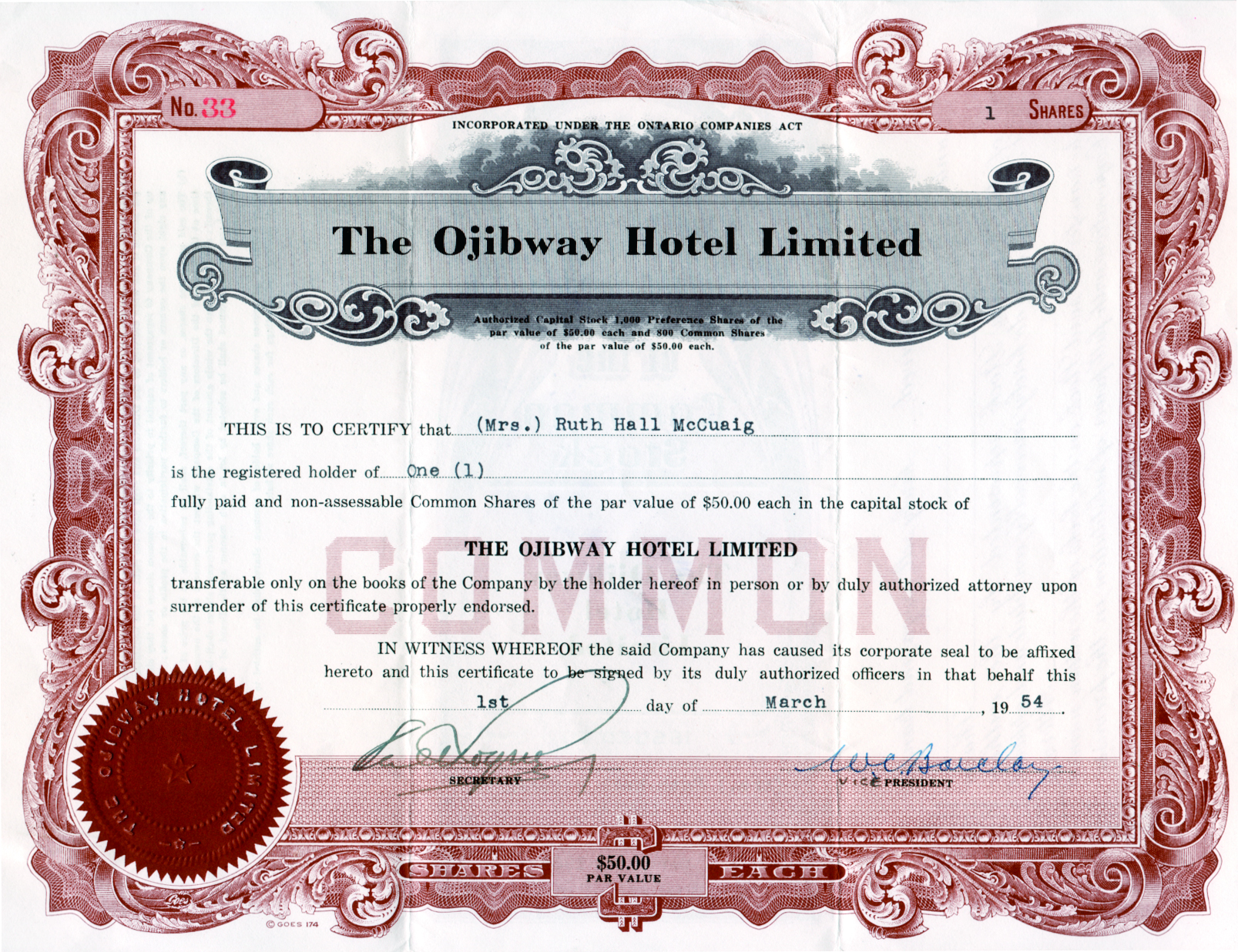

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, shares were issued to finance the ongoing operations of the hotel. This had more to do with fundraising than with investment, for there were certainly more profitable ventures than a big old resort. But the islanders wanted the Ojibway to continue to be run as always. None of the investors expected to make any money. And, as a matter of fact, they didn’t.

The picture of a happy young aqua-boarder was on the front of the postcard (above, left) that Hamilton Davis sent his niece informing her that he had sold the hotel. It was poignant that Hamilton chose a carefree scene to convey sad news. But although it was the end of an era, he knew that the spirit of summer at the Ojibway would prevail and so would the music and the fun.

The purchase price was $80,000 and common shares were issued at $50 each. Eventually, there were over a hundred shareholders, all of whom were islanders. “Percy Woodward has bought $2,000 worth – also Jack Perks,” Davis wrote in his letter to Frances. It had been agreed that no individual could own more than $2,500 worth of stock, and “they will not sell stock to guests of the hotel,” Davis wrote. “They are afraid the guests would have asked special favours.”

Buying a hotel was one thing, but running one was something else altogether. And once the commitment and the energies of Hamilton and Irene Davis were subtracted from the equation, the challenges of operating a hotel – in particular, an aging hotel – became steadily clearer.

The hotel was busy enough. There was a heady postwar energy – a kind of optimism that lent itself to the fun of summer holidays. As actress Araby Lockhart, who worked at the Ojibway in the late 1940s, put it: “If you were alive, you had to live as if for those who hadn’t made it.”

By the time the slow, leisurely holidays, on which the Ojibway had built its reputation, were becoming a thing of the past, the hotel’s buildings were aging and becoming more dependent on constant repair. A case in point was its grocery store (above), anchored by chains to prevent it from falling into the lake.

After the war, there was an understandable tolerance for youthful high spirits. For a few summers, in the late 1940s, for instance, the hotel’s ice house was taken over by teenagers every August, once enough ice had been removed to provide some room. They would sit inside, on top of the sawdust-covered ice blocks for an hour or so at dusk – led by Scott Symons and his accordion – singing such popular tunes as “The Persian Cat,” “The Wild West Show” and “The Titanic” until the night watchman eventually came along and told them, “Pipe down!”

In those days, Bert Bruckland still ran the dock, but he was easing his way toward retirement. He spent most of his time overseeing things from his rocking chair. After Hamilton Davis had sold the place, a series of managers were hired to run it, but maintaining the old buildings became increasingly costly. Tastes in holidays shifted away from the Ojibway’s small, modestly appointed rooms and unfussy home-cooked meals. The bustling, happy postwar years obscured a reality that only became apparent at the end of each season, when accounts payable and accounts receivable were accurately tallied up. For the hotel’s board of directors, it was becoming clear that things were not unfolding as they had hoped. “The hotel company lost over $5,000 before depreciation in the summer of 1950, and after depreciation the loss is more like $10,000,” wrote H. W. Larkin, president of the Ojibway Hotel Limited, to the shareholders in 1951. In 1954, in a note to L. B. Prior, among others, an obviously worried Senator Campbell wrote: “I am having a stag luncheon at my cottage on July 24 for a few of the islanders and hotel residents. I should appreciate it very much if you could be present, as I should like to discuss some of the problems that have arisen in connection with the Ojibway Hotel. As you probably know, a number of us have put up considerable money to provide for capital improvements and keep the hotel operating.”

It wasn’t easy to keep the place going. In the 1950s, shifting demographics, improved transportation and rising labour and maintenance costs did not favour the kind of slow, gentle, old-fashioned holiday the Ojibway offered. By the time people could easily get to and from Pointe au Baril for a weekend visit, the long and unhurried vacations on which Hamilton Davis had based his hotel’s success had become as outdated as steamer trunks, linen suits and long white dresses. The cost of maintaining the buildings remained high, and the club often relied on the kindness and largesse of islanders for its survival.

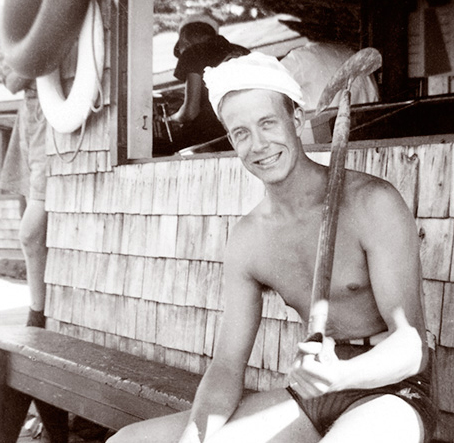

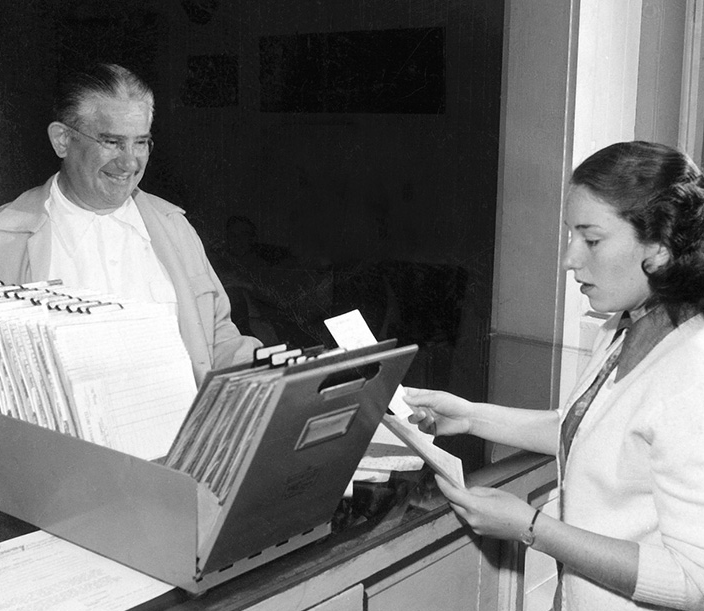

In the 1950s, the Ojibway’s slowly descending fortunes were reversed with the arrival of a new, dynamic management team: the MacLennan family (top photo, right: from left, Mildred, Sondra, Taylor and Harry). Harry “Mac” MacLennan was the experienced hotelier, but it was his daughter, Sondra (pictured left, with the Ojibway staff, and top left, greeting guests) who was, effectively, the hotel’s manager. She threw herself into the task of returning the Ojibway to its glory days, assisted by the enthusiasm of her youthful employees (above).

On February 1, 1951, in a letter to the shareholders of the Ojibway Hotel Limited, H. W. Larkin wrote: “It is now over seven years since the present shareholder group purchased from Mr. Davis and his associates the capital stock of the Ojibway Hotel Limited. Your directors have now reached the conclusion that the operation of the hotel under the present system is not satisfactory.” But up its sleeve, the board had what it hoped would be a solution.

“Girl of 21 takes over famed Ojibway Hotel. Seventy under her orders,” read the headline in the Toronto Daily Star on June 14, 1951. “Fresh from Cornell University School of Hotel Administration at Ithaca, New York. Miss MacLennan isn’t tackling a tough job on looks and personality alone. She was born in the hotel business and grew up in it.”

The “girl” was the daughter of Harry MacLennan, a friendly bear of a man known, it seemed, to everyone as “Mac,” who had managed the King Edward in Toronto and the Royal Connaught in Hamilton. Vice-president of the Cardy Hotels chain, he knew about the Ojibway and about Pointe au Baril as a result of his contacts in Toronto and Hamilton. He knew of its past and recognized its potential, and he suggested that his daughter, Sondra, with the support of his wife, Mildred, and his son, Taylor, take on the management of the Ojibway. He would function in an advisory capacity, often by long distance, from Bermuda. “Friday, when her dad takes to the air once more,” reported Dick Ryder of the Star, “Sondra MacLennan will be left in charge of preparations to open the hotel…. Already, reservations totalling 80 percent of last year’s volume are in, and it looks like a busy summer for Sondra and her staff of 70, of whom 14 now are at work painting, cleaning and building.”

Few details escaped Sondra MacLennan (above), and if a job needed to be done, she often did it herself. Under her management, Ojibway traditions were maintained, but innovation was never ruled out, and among the most striking improvements was the refrigerated container that trucked fresh meats and produce from Toronto twice a week and was then ferried to the hotel from Pointe au Baril Station (top right).

It was apparent to the MacLennan family that simply running the Ojibway – as challenging as that was – would not be nearly enough to return the place to the standard of its glory days, and there was a certain amount of catching up to be done. “There were jars of peanut butter on the table,” Sondra recalls. “The guests would bring all their special foods to the dining room. Otherwise, they wouldn’t get what they wanted to eat. And they were serving meals on these little round birch-bark placemats. If something spilled on them, you couldn’t wash them. They were there for years. Not very nice. And the dining-room floor was so dirty. It had about four coats of paint on it. We had to scrape it down. Mum asked a senior executive of Procter and Gamble, a guest from Cincinnati, what we could put on the floor so the waitresses wouldn’t slip. And he came up with some paints for the floor that would work for us. It had a bit of grit in it.”

There were some islanders who felt that the MacLennans – with their French pastry chef, ice sculptures in the dining room and linens in place of the sweet-grass placemats – were changing things too radically at the old hotel. Others felt they were simply returning to the Ojibway’s former high standards. Certainly, the care they brought to a task such as repainting the dining-room floor was indicative of the attention to detail that marked the MacLennans’ 10 summers at the Ojibway. Money was spent and the hotel was whipped back into shape. A new chef was hired. Roger Rusterholtz had trained in France, had worked at the Royal Connaught in Hamilton and would be remembered by everyone who worked anywhere near him as “extremely temperamental – a real French chef – very volatile.” Rusterholtz managed only one summer in the culinary outpost of Pointe au Baril, but he established the Sunday buffet that became so popular with cottagers and guests alike. He presided over the dining room in his high white chef’s hat. Guests appreciated the white tablecloths, the pressed linen napkins and the dauphine potatoes.

Not very much older than her employees and by all accounts a popular manager, Sondra MacLennan (in plaid dress, left) was still able to insist that the Ojibway staff be neatly dressed, well groomed and polite, and that the guests came first. She frequently consulted her dad, Harry (below), for his business acumen, and also relied on longtime Ojibway veteran, Bert Bruckland (bottom) for his advice and experience.

One of Harry MacLennan’s most striking innovations was a refrigerator truck – bright red, often seen on Toronto’s Yonge Street during those summer months. It brought fresh produce from St. Lawrence Market to the Ojibway twice a week. The insulated container was unloaded at the Pointe au Baril Station, craned onto a barge and then towed by Evoy’s Taxi Service out to the island. It was, for many years, a fixture at the Ojibway dock – almost as much of a landmark as Claude Bragdon’s tower.

Bellhops wore khaki uniforms and bow ties. The waitresses’ uniforms were pale yellow with white collars, and the girls were not allowed to wear trousers or shorts. Kathy Metcalfe, now a cottager, remembers having to wear stockings in the office. Sondra developed a firm but friendly working relationship with her employees, many of whom were only a few months younger than she was. During the next 10 years, the running of the Ojibway was truly a family affair. Mrs. Mildred MacLennan, her son, Taylor, and daughter Tanya were all part of the team. Even Bert Bruckland, looking back in 1951, seemed pleased with the MacLennans’ direction. “We were filled up in 1906 and even had to put up tents,” he said with cheerful bluster. “We’ve been going strong ever since.”

It was, in many ways, a second golden era for the Ojibway – in every respect perhaps, except one. The MacLennans were wise enough to realize that improving standards did not mean bringing in unnecessary innovation. The food was better than it had ever been; the service was back to the level that Irene Davis had insisted on when the dining room fell under her watchful eye. But as heartfelt as the dedication of the MacLennan family was, it became increasingly difficult to make the dollars and cents add up. People wanted a different kind of holiday, and by the end of the 1950s it was apparent that the days of the Ojibway Hotel were numbered.

The Ojibway’s creaking staircases, wooden floors, shadowy

corners, high, mysterious-looking windows and Claude Bragdon’s striking tower have always been the perfect setting for Georgian Bay ghost stories.

{ Ghosts }

THINGS THAT GO BUMP

And if, late on a summer night, when the embers are glowing in the old stone fireplace and the shutters are rattled by the wind, when talk turns to the strange things that are sometimes seen on Georgian Bay, you might hear of the ghosts of the Ojibway. There are the nights when a lantern has been seen in the tower, held by a lady dressed in white. And there have been reports of a ghostly presence – a man, it is thought – moving along the creaking boards of the third floor of the Ojibway’s main building. Are these spirits from long ago?

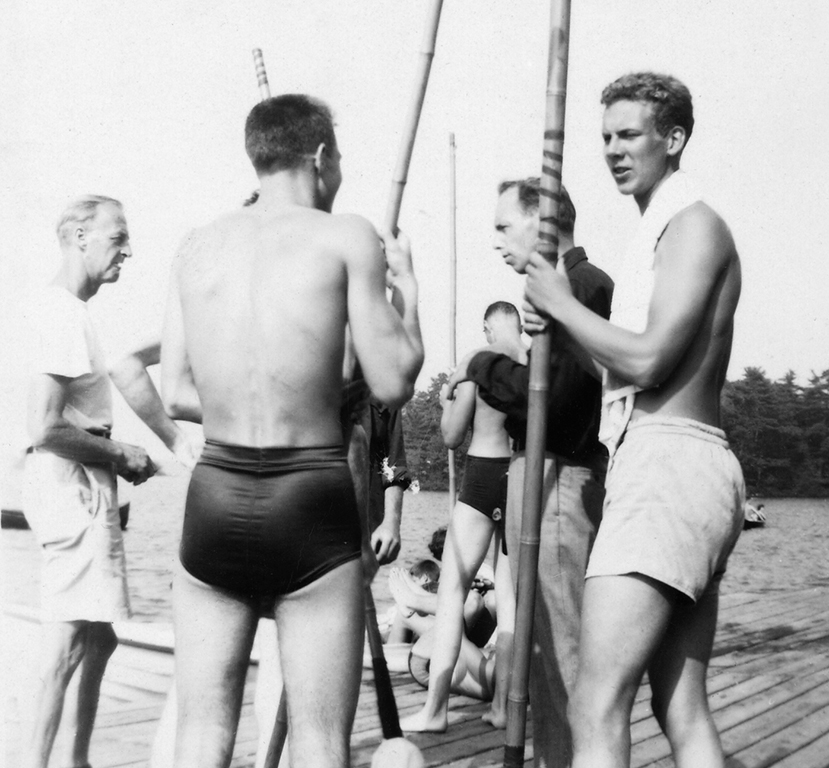

Work and fun: constants for Ojibway staff.

How Goes the Battle? –

It was a question that Miss Cowan, the head of the Ojibway dining room in 1940s, was famous for asking. Her waitresses heard it every day. But it might as well have been a question put to the entire staff. Working at the Ojibway has always been a bit of a battle, but a battle that has its rewards. There have always been pranks and parties, summer romances and lasting friendships. Joy Wright, who worked as a waitress at the Ojibway in the late 1930s and early 1940s, remains convinced that the staff always had more fun than the guests. Still, it wasn’t easy work, and the waitresses, guides, bellhops, laundresses, housekeepers, fish cleaners of the hotel and, more recently, the counsellors and the staff of the office, snack bar, grocery store and gift shop of the club have more than earned their keep. They’ve always been the spirit of the Ojibway.

“When it was rough on the bay, the guests were around and kept us busy. We always liked it when they went fishing.””

And a good time was had by all.

On Your Marks –

In the summer of 1907, the first regatta was held at the newly built Ojibway Hotel. Twenty years later, the Pointe au Baril Islanders’ annual competition had become such a success it was expanded into two-day-long events: the junior regatta, usually held on the last Saturday of July, and the senior regatta, usually held on the first Saturday of August. Ever since, good sports of all ages have battled for supremacy in canoeing, rowing, sailing, swimming, diving – to say nothing of tilting, crabbing and gunwale bobbing. Hamilton Davis never lost sight of the fact that the success of his hotel depended, in large part, on its being embraced by the ever-growing summer community of cottagers. Although he was an avid canoeist and sailor, the trophy he donated to the annual regatta was for the “open speed-boat race” – an event inevitably won by an islander and not a hotel guest.

“When I was seven or eight, I won first prize in the rowing. I was the only entry. There’s no romance in rowing.””

continue to { Chapter 5 }